The EU as a global frontrunner in promoting gender equality in trade?

The European Union (EU) often projects itself as a frontrunner in promoting gender equality. It often takes a normative approach and teaches others on gender issues (European Commission, 2015; J. V. D. Vleuten, 2017). Historically, the EU institutions started promoting gender equality internally before expanding beyond its member states. Already in 1957, gender equality was introduced in the Treaty of Rome. Article 119 included the principle of equal pay for men and women. It ensured that lower wages for female workers would not harm the competition. In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam defined gender mainstreaming as a core principle obliging all European institutions to encompass gender dimensions in their policy areas – including trade policy (Weiner & MacRae, 2014, pp. 4–5). In the past decades, the EU has actively pursued a strategy of trade liberalization. However, liberalizing trade has gender-differentiated effects. Whereas male-dominated export-oriented industries tend to profit, small enterprises or farms, which mostly employ or are run by women, are not sufficiently equipped to compete internationally. Further, new jobs for women such as in the textile sector are often low-skilled, labor intensive and low-paid (European Parliament Research Service, 2019; Garcia, 2021; Garcia & Masselot, 2015).

Addressing this issue, the EU has included general human rights clauses in free trade agreements (FTAs) since the 1990s. More recent agreements also include trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters, which refer to international standards on labor rights which entail gender-related aspects such equal pay and the prohibition of discrimination. While the signing parties committed themselves to abiding to these provisions, there is no effective sanctioning mechanism in case of violating them. TSD provisions have always been excluded from the general dispute settlement mechanism. In addition, the European Commission considered gender aspects more concretely in its sustainability impact assessments which were conducted for many agreements since 2002 (European Parliament Research Service, 2019).

Lately and for the first time ever, the negotiations on the modernization of the EU-Chile Association Agreement (ECAA) resulted in including a chapter concerning cooperation related to gender (European Commission, 2002; Garcia, 2021; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019). Hence, it may be summarized that the EU’s gender-blind practice of trade has only recently become more gender-sensitive (Garcia, 2021). However, the EU still prides itself in being a global leader in the field of gender equality promotion. Concerning international commerce, former trade commissioner Malmström communicated that the EU would consider gender in all impact assessments that are conducted and referred to binding commitments on gender equality in bilateral trade deals (Malmström, 2019). Therefore, it may be wondered whether this self-painted picture of the EU as a global front-runner in gender equality promotion is accurate. In other words, it is worth exploring whether the EU is the most ambitious gender equality promoter in trade. Based on the EU’s normative aspirations combined with its market and regulatory power, it is hypothesized that the EU is willing as well as able to negotiate more advanced FTAs than other like-minded actors.

In this post I take a triangular approach to address the research puzzle. Aiming to assess the level of ambition relatively to other progressive actors, the EU is compared to Canada and Chile. These countries are chosen because both signed trade agreements with the EU in recent times as well as they included a comprehensive gender equality chapter in their bilateral Trade and Investment agreement (Government of Canada, 2017; Morgan, 2017). I further explore gender-related aspects in the three agreements individually before contrasting their levels of ambition. A cross-case analysis provides the ground for assessing whether the EU is the most ambitious global actor in promoting gender equality in trade.

Analytical Framework

The EU’s aspiration to promote gender equality has often been explained by its normative self-perception. In his seminal work Ian Manners described the EU as a normative power, which bases its policy formulations on core values and projects these in its foreign policies (Manners, 2002). A normative power approach focuses explicitly on questions such as whether, what and how should the EU advance gender equality in its external relations (Debusscher & Manners, 2020). While Manner’s approach was extensively critiqued to various degrees (Diez, 2004; Hyde-Price, 2006; Noutcheva, 2009), it provided valuable insights in the debate on gender equality. Various scholars employed the normative power approach when investigating the rationale of gender mainstreaming in the EU’s discourse (David & Guerrina, 2013) or with regard to the development policy (Debusscher, 2011). Further, Debusscher & Manners stated that it needs a rethinking of the EU as global gender actor considering a holistic intersectional and inclusive approach of “gender+” (Debusscher & Manners, 2020).

In the literature on EU trade policy, understandings of the EU as a “market power” or a “regulatory power” have shaped the discourse. The former describes the EU’s role as exercising power through the externalization of economic and social policies which affect international partners (Damro, 2012). The latter builds on the EU’s extensive regulatory power resources such as its large market and regulatory capabilities to shape global norms and regulations (Newman & Posner, 2015; Young, 2015). These are arguably useful to promote gender equality through a regulatory manner being backed by market power. This fits in the Commission’s description of the EU as a global rule maker (European Commission, 2007). Further, normative, market and regulatory power have been contrasted in different case analyses (Orbie, 2014; Orbie & Khorana, 2015). Considering these approaches in the context of gender equality promotion, I hypothesize that the EU applies its market and regulatory power to project its normative understanding of gender equality in trade agreements. In other words, it is assumed that the EU is the most advanced gender actor because it is driven by strong normative convictions and equipped with sufficient market and regulatory power to implement its ambitions in trade agreements.

To test this hypothesis, I employ a triangular approach. Recognizing that Canada, Chile, and the EU are relatively advanced in promoting gender equality in comparison to other countries, the respective bilateral trade relations are explored (Garcia, 2021). Firstly, the bilateral trade agreements are scrutinized individually. Taking an inductive approach, it is assessed whether, and if so, to what extent gender equality is addressed. Based on this, criteria are defined to assess gender equality aspects more comprehensively. Secondly, a cross case analysis offers data to draw conclusions about which country shows the highest ambitions on gender equality in its bilateral trade agreements.

Analysis

Beginning with the modernized EU-Chile association agreement (ECAA), both parties agreed upon dedicating a chapter on the cooperation related to gender. Updating the original legal document signed in 2002, in the latest version article 45 includes the commitment to ensure equal participation of men and women in all sectors encompassing the political, economic, and social life. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of women’s ability to exercise their fundamental rights. It also entails gender mainstreaming when stating that gender and gender-related issues shall be considered at every level and in all areas of cooperation. Finally, it promotes the adoption of positive measures in favor of women which leaves room for interpretation of what this actually concerns (European Commission, 2002).

Reviewing the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada, it is noticeable that it does not include any explicit provisions on gender. The legal text of more than one thousand pages only mentions gender once as a grounds for wrongful discrimination in the chapter on treatment of investors (European Commission, 2017). However, both parties established the CETA Joint Committee which developed nine recommendations on trade and gender. These include making trade policies more gender-responsive, exchanging best practices on the involvement of women in trade and collecting gender-disaggregated data to better assess the impacts of CETA. In addition, the importance of women’s access to and the benefit from the opportunities created by the CETA are highlighted. Both parties also commit themselves to pursue the Sustainable Development Goal 5 to achieve gender equality and to empower all women and girls as well as the recall of international conventions guaranteeing women’s rights (European Commission, 2018). The recommendations are further specified in action items which are included in the EU-Canada Work Plan (European Commission, 2020).

Finally, the Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) is subject of analysis. The CCFTA was enforced in 1997 and complemented by amending agreements in 2017. This modernized CCFTA entered into force in 2019 and includes a trade and gender chapter (Government of Canada, 2021a). In its general provisions, the CCFTA gender chapter highlights the importance of including gender perspectives in trade as well as of providing equal opportunities for the participation of all sexes. This encompasses the elimination of gender discrimination and removing barriers. Both parties reiterate women’s rights codified in international agreements and commit themselves to exchanging knowledge about best practices. Additionally, a trade and gender committee was established to define and to manage the cooperation activities. Finally, it is stated that the chapter is not subject to the dispute resolution mechanism (Government of Canada, 2017).

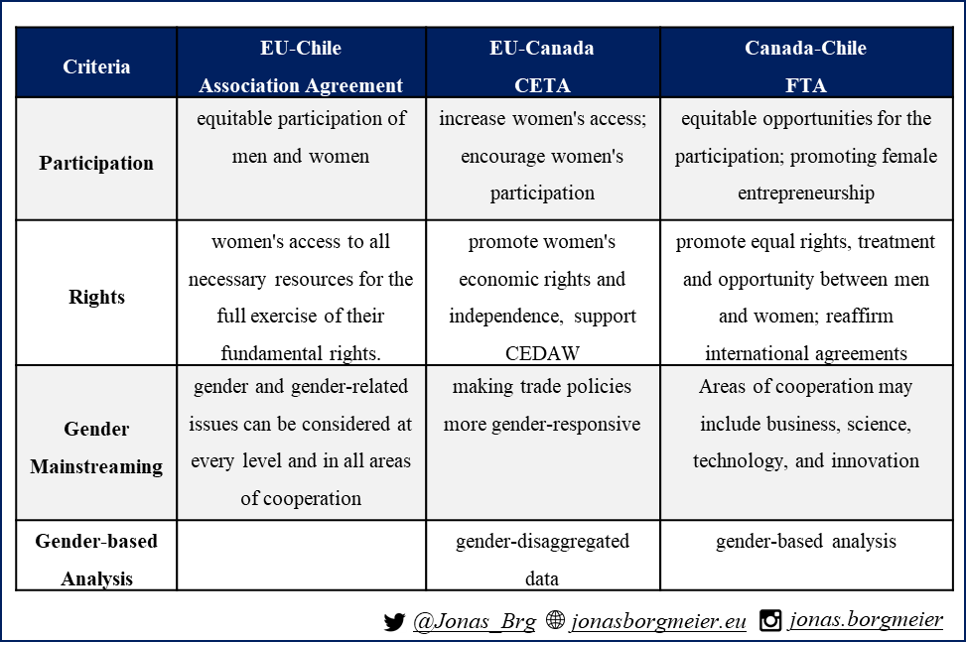

Reflecting upon the first step of the analysis, it is noticeable that the ECAA and the CCFTA include a chapter on trade and gender while the CETA does not. Before debating which conclusions can be drawn regarding the ambitions of different actors, the range of analysis is expanded. The inductive exploration of gender-related aspects in the agreements allows for developing criteria about the nature of gender equality being addressed. These include aspects such as women’s rights, participation, or gender-based analyses. They are part of an analytical structure to assess gender equality in more qualitative terms. In the following, the relevant documents of the agreements are assessed on the basis of the criteria. Table 1 offers an overview of the results. It can be seen that the documents address almost all criteria. The chapter on cooperation related to gender in the ECAA reflects the importance of women’s participation, women’s rights, and gender mainstreaming. The latter explicitly states all areas of cooperation which indicates a holistic rationale. However, there was no reference to conducting gender-based analyses. The recommendations of the CETA Joint Committee are more detailed and address all criteria. The modernized CCFTA also takes a rather holistic approach to gender equality and considers all criteria.

Based on the individual analysis of the bilateral trade agreements, a comparative approach is used to test the hypothesis that the EU is the most ambitious gender actor. Regarding the incorporation of gender equality in trade agreements, the modernized ECAA contains a chapter on cooperation related to gender. However, the CETA does not. More strikingly, the agreement between Chile and Canada (CCFTA) contains an even more comprehensive gender chapter than the ECAA. Contrasting the provisions based on the developed criteria of participation, rights, gender mainstreaming and gender-based analysis, it is noticeable that all three agreements reflect a relatively similar understanding of gender equality. The fact that the ECAA does not address gender-based analysis could be explained by the more abstract wording in the trade agreement, while the more comprehensive list of recommendations of the CETA Joint Committee allows for more detailed description by its nature.

Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that the ECAA most explicitly describes the characteristics of gender mainstreaming emphasizing cooperation in all areas and on all levels. The CCFTA defines this in a more practical manner while the CETA provision keep a rather narrow focus on trade policies. In addition, the importance of equal participation and rights becomes visible in all documents.

Comparing the EU to Canada and Chile, it can be concluded that the EU is not the most advanced gender promoter in trade agreements. While its understanding of gender equality is relatively similar to the one of other countries, it fails to incorporate gender equality in the CETA agreement. It may be speculated why Chile managed to conclude a more ambitious agreement with Canada than the EU. Considering the balance of normative, market and regulatory power, it seems unlikely that the CCFTA includes a gender chapter because of Chile’s market and regulatory power which is arguably inferior to the respective power of the EU.

In other words, it would be implausible to argue that the EU lacks market and regulatory power to convey its normative aspirations. Hence, the EU’s level of ambition as a normative actor needs to be questioned. Negotiating a comprehensive agreement with a like-minded partner such as Canada arguably provides a great opportunity to raise the bar and to make ambitious rules on gender equality. Failing to do so whilst celebrating the incorporation of a gender chapter in the ECAA raises doubts about the EU’s ambition and shows a gap between rhetoric and practice. Rather than making the rules in the CETA, the EU appeared to take the rules from Chile in the ECAA. It can be argued that the self-perception of a rule-maker clashes with the reality of a rule-taler. The results of the analysis allow for the conclusion that the EU did not live up to its normative aspirations to be a global promoter of gender equality in trade.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the EU’s general self-perception as a global gender actor, in this blog post I addressed the EU’s role in being a leading promoter of gender equality in trade. Based on normative aspirations in combination with the EU’s market and regulatory power, it was hypothesized that the EU is willing as well as able to negotiate more advanced FTAs in the sphere of gender equality than other like-minded countries. I conducted a triangular approach to the analysis by comparing the EU with Chile and Canada. Firstly, the respective bilateral trade agreements were explored inductively with regard to their focus on gender equality. Building upon this, criteria for assessing the definition of gender equality were developed and applied to the FTAs individually. Secondly, the results were compared to draw conclusions about the level of ambition put forward by the three actors to promote gender aspects. This analysis has shown that the EU and Chile as well as Chile and Canada included a chapter on gender equality while the CETA between the EU and Canada did not. The latter only offers a list of recommendations on the matter issued by the CETA Joint Committee on trade and gender.

I further developed four criteria to contrast the understanding of gender equality in the documents. All offer a rather holistic definition of gender equality addressing the criteria participation, rights, gender mainstreaming and gender-based analysis – referring to them either explicitly or implicitly. It can be summarized that the EU failed to incorporate gender equality provisions in the agreement with Canada while Chile did. Considering the concepts of market and regulatory power, it seems unlikely that the Chilian is superior to the European. Therefore, it can be argued that the EU was not willing to negotiate more ambitious FTAs than other like-minded actors and thereby, fails to live up to its normative self-perception. Rather than making the rules, the EU appears as a rule-taker in the promotion of gender equality in trade. This case-based analysis contributes to the literature on the EU as a global gender actor in general and in particular in the field of the EU’s external economic policies. To substantiate the assessment further trade agreements with like-minded as well as indifferent or opposing trading powers on the matter should be conducted in future research. It may be of particular interest to explore what provisions the future EU-New Zealand trade agreement may include (European Commission, 2021c). Further research should also explore explanations for the alleged lack of ambition by the EU.

In my opinion, it is worrisome that the EU is not at the forefront in implementing gender equality provisions in its trade agreements with like-minded countries. It can be reasonend that FTAs with partners opposing to gender equality may not include gender chapters despite the alleged normative, market and regulatory power of the EU. However, the EU fails to walk the talk even in more benign circumstances. Hence, it needs to be further investigated which factors cause the discrepancies. What do you think?

Thank you for investing your time in reading this post. If you have feedback, questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to me on twitter.

References

Damro, C. (2012). Market power Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(5), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.646779

David, M., & Guerrina, R. (2013). Gender and European external relations: Dominant discourses and unintended consequences of gender mainstreaming. Women’s Studies International Forum, 39, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2012.06.005

Debusscher, P. (2011). Mainstreaming gender in European Commission development policy: Conservative Europeanness? Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2010.10.001

Debusscher, P., & Manners, I. (2020). Understanding the European Union as a Global Gender Actor: The Holistic Intersectional and Inclusive Study of Gender+ in External Actions. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919899345

Diez, T. (2004). Constructing the Self and Changing Others: Reconsidering `Normative Power Europe'. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 33(3), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298050330031701

European Commission. (2002). Free Trade Agreement. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:f83a503c-fa20-4b3a-9535-f1074175eaf0.0004.02/DOC_2&format=PDF

European Commission. (2007). The External Dimension of the Single Market Review: Commission Staff Working Document. http://aei.pitt.edu/45898/1/SEC_(2007)_1519.pdf

European Commission. (2015). International Women’s Day [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_15_4573

European Commission. (2017). Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22017A0114(01)&from=EN

European Commission. (2018). Recommendation 002/2018 of 26 September 2018 of the CETA Joint Committee on Trade and Gender. http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/september/tradoc_157419.pdf

European Commission. (2020). CETA Trade and Gender Recommendation: EU-Canada Work Plan 2020-2021. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2020/september/tradoc_158945.pdf

European Commission (Ed.). (2021a). Canada - Trade - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/canada/

European Commission (Ed.). (2021b). Chile - Trade - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/chile/

European Commission (Ed.). (2021c). Towards an EU-New Zealand Trade Agreement. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/in-focus/eu-new-zealand-trade-agreement/

European Parliament Research Service. (2019). Gender equality and trade. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2019/633163/EPRS_ATA(2019)633163_EN.pdf

Garcia, M. (2021). Trade policy. In G. Abels (Ed.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge handbook of gender and EU politics (pp. 278–289). Routledge.

Garcia, M., & Masselot, A. (2015). The Value of Gender Equality in EU-Asian Trade Policy: An Assessment of the EU’s Ability to Implement Its Own Legal Obligations. In A. Björkdahl, N.

Chaban, J. Leslie, & A. Masselot (Eds.), Importing EU Norms: Conceptual Framework and Empirical Findings (pp. 191–209). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13740-7_12

Government of Canada (Ed.). (2017). Appendix II – Chapter N bis–Trade and Gender. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/chile-chili/fta-ale/2017_Amend_Modif-App2-Chap-N.aspx?lang=eng

Government of Canada (Ed.). (2021a). Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/chile-chili/index.aspx?lang=eng

Government of Canada. (2021b). Trade and Gender: The Canada-Chile Story. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/gender_equality-egalite_genres/trade_gender_ccfta-alecc-commerce_genre.aspx?lang=eng

Hyde-Price, A. (2006). ‘Normative’ power Europe: a realist critique. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500451634

J. V. D. Vleuten (2017). The Merchant and the Message: Hard Conditions, Soft Power and Empty Vessels as Regards Gender in EU External Relations. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Merchant-and-the-Message%3A-Hard-Conditions%2C-Soft-Vleuten/a890486cd4389d89944d5eae73c5b212a0dea14a

Malmström, C. (2019). Why don’t women benefit from international trade as much as men? EURACTIV.Com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/opinion/why-dont-women-benefit-from-international-trade-as-much-as-men/

Manners, I. (2002). Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00353

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019). Handbook Sweden’s feminist foreign policy. https://www.government.se/4ae557/contentassets/fc115607a4ad4bca913cd8d11c2339dc/handbook---swedens-feminist-foreign-policy.pdf

Morgan, S. (2017, June 21). EU wants gender chapter included in Chile trade deal update. EURACTIV.Com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/eu-wants-gender-chapter-included-in-chile-trade-deal-update/

Newman, A. L., & Posner, E. (2015). Putting the EU in its place: policy strategies and the global regulatory context. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1316–1335. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046901

Noutcheva, G. (2009). Fake, partial and imposed compliance: the limits of the EU’s normative power in the Western Balkans. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(7), 1065–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903226872

Orbie, J. (2014). Promoting Labour Standards Through Trade: Normative Power or Regulatory State Europe? In R. G. Whitman (Ed.), Palgrave studies in European Union politics. Normative power Europe: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 161–184). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230305601_9

Orbie, J., & Khorana, S. (2015). Normative versus market power Europe? The EU-India trade agreement. Asia Europe Journal, 13(3), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-015-0427-9

Weiner, E., & MacRae, H. (Eds.). (2014). The persistent invisibility of gender in EU policy (18th ed.). http://eiop.or.at/eiop/pdf/2014-003.pdf

Young, A. R. (2015). The European Union as a global regulator? Context and comparison. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1233–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046902

Thank you for providing the cover photo Dursun Aydemir/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images