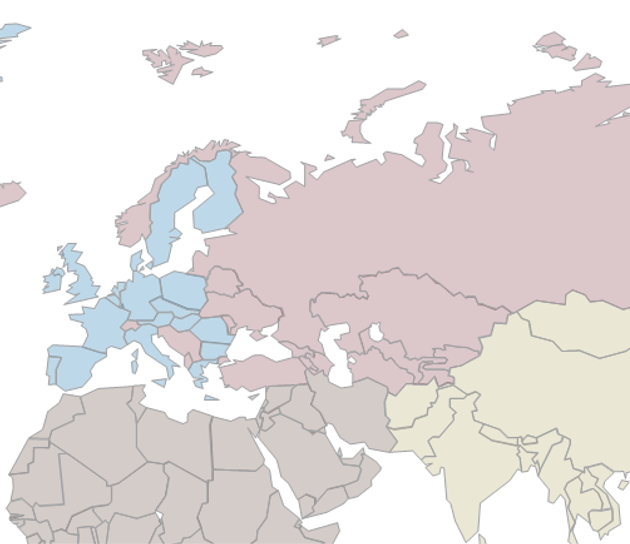

Russian hegemony in Eastern Europe and MENA?

Ever since Vladimir Putin became President, a U-turn in Russia’s foreign policy could be witnessed. The hopes about a democratizing and cooperative Russia with closer ties to the West turned into more troubled and hostile relations. Ranging from the annexation of Crimea in the Ukraine conflict to the determined support of Syrian President Assad, Russia has taken a more active and coercive role in neighboring regions (Delcour, 2018, p. 17). In this blog post, I argue that Russia’s actions in Eastern Europe as well as in the region of North Africa and the Middle East (MENA) can be explained through a realist approach. I show how Russian President Putin’s rationale is shaped by a realist world view and that Russia prioritizes geopolitical interests in the near neighborhood and beyond. To provide a comprehensive context, firstly, Russia’s role in Eastern Europe and the MENA region is reflected upon. Secondly, the main realist argument is developed by assessing the three realist characteristics of balance of power, geoeconomic interests as well as use of force. Finally, the Russian impact on the policies of the European Union (EU) are analyzed by presenting constraints and possibilities for EU action in the regions. While I recognize alternative explanatory approaches but I focus on the realist approach as it arguably provides the best explanations.

Russia’s role in Eastern Europe and MENA

Russia’s role as a key player in Eastern Europe as well as the MENA region can be traced back to the long history of engagement of former Russian entities. While it is not within the scope of this post to analyze the past two centuries, it is important to be aware of them when analyzing the intensified actions of Russia in the past two decades. In the following, the Russian involvement in both regions is briefly introduced and subsequently compared and contrasted. Focusing on Eastern Europe, Russia was faced with a wave of color revolutions in the post-Soviet space in the 2000s which were partly motivated by the will to establish closer ties with European countries. Opposing to this, Russia decided against joining the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) of the EU which complicated the cooperation within the region (Raik, 2019, p. 51). Russia set up a complex and multifaceted security structure of interdependences with sovereign post-Soviet countries in its so-called ‘near abroad’ (Delcour, 2018, pp. 15–16). Considering the degree of institutionalization in the region, the Commonwealth of Independent States was founded in 1991 as a rather weak intergovernmental organization of post-Soviet countries to facilitate cooperation in economic, defense and foreign policy. Additionally, the Collective Security Treaty Organization was set up to manage collective defense in Eurasia. In 2015, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) was created as a customs union of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan to facilitate economic integration (Casier, 2021; Noutcheva, 2018, p. 317). Addressing the nature of Russia’s relations with states in Eastern Europe, there appears to be a cleavage between countries that traditionally favor close ties with Russia and countries that are rather skeptical. Regarding the former, Belarus is traditionally closely allied with Russia whereas Ukraine and Georgia can be considered as examples of the latter. They have a recent history of military confrontation and foster relations with other actors such as the EU (Delcour, 2018, p. 22; Raik, 2019, p. 59). The protests in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan in 2020 as well as the Second Karabakh war and the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine demonstrate the instability in the region and challenge Russia as a regional power (Casier, 2021). In the MENA region, Russia’s engagement in the past years has been understood as a return to the region (Frolovskiy, 2019). Having withdrawn in the post-Cold War years, President Putin started a new diplomatic approach in the mid-2000s. While it was mostly perceived as an irritant to Western engagement in the beginning, Russia has become a critical interlocutor for most states in the region (Casier, 2021). Russia’s importance is demonstrated by the fact that the UN-brokered deal to remove and destroy Syria’s chemical weapons and the Iran nuclear deal would have been impossible to achieve without Russian involvement. Referring to the degree of institutionalization, it needs to be pointed out that there is no Russian-lead multilateral organization (Fawcett, 2018, p. 72). Russia rather maintains close bilateral relations. For example, Russia supported the Syrian Assad regime militarily and diplomatically. Russian forces provided air-support for the regime while its diplomats vetoed the authorization of military action against it in the UN Security Council (Dannreuther, 2019, p. 739; Rumer, 2019). Further, it is noticeable that Russia has close ties with Iran as well with Israel. President Putin also cultivates his relationship with Turkish President Erdogan despite various conflicting views and has revived exchanges with Egypt (Dannreuther, 2019, pp. 726–727). In summary, Russian relations with Eastern Europe and the MENA region have quite distinct characteristics. While there is a relatively high degree of Russian-led institutionalization of state activities among post-Soviet countries – except for countries like Ukraine and Georgia, the MENA region does not offer similar multilateral institutions. In terms of the general nature of relations, Russia maintains well-functioning and pragmatic working-relations with most MENA countries despite enmities among them. The post-Soviet area is more divided between close Russian allies and critics of Russian actions.

Explaining Russia’s behavior through realist rationale

Having introduced the context of Russian engagement in Eastern Europe and the MENA region, this section engages with this post’s core argument that a realist rationale offers great explanatory power to understand Russia’s activities. Before analyzing Eastern Europe and the MENA region, the main realist characteristics are introduced. A realist perspective essentially focuses on the principles of statism, survival and self-help and generally emphasizes the importance of hard (military) power. In the condition of anarchy, states follow their national interest of survival and strive to expand their power to gain as much sovereignty as possible (Dunne & Schmidt, 2020, p. 113; Hyde-Price, 2006, p. 218). Geopolitics can be seen as an application of a realist approach. Geographical factors such as certain territories, routes and resources are perceived as vital for the national interest in a geopolitical sense. Geoeconomics further considers economic interests as essential part of national security. Consequently, states strive to maximize military, economic as well as political power resulting in a zero-sum competition for spheres of influence (Raik, 2019, p. 55). On the one hand, great powers are constantly testing the balance of power being a key feature of realist thought (Mearsheimer, 2017, p. 52). On the other hand, a small country is forced to align with a major power because of limited capabilities to defend itself. In addition, realists consider the use of force and military threat justified instruments to pursue national interests (Raik, 2019, p. 55). Finally, the balance of power, geoeconomic interests as well as the use of force can be defined as main characteristics of realist thought to assess Russian actions.

With respect to Eastern Europe, Russia acts according to various realist principles. Firstly, Russia considers the balance of power in the region. Former Russian President Medvedev has declared Russia’s ‘privileged interests’ in the region, which evidently expresses Russian understanding of Eastern Europe as its sphere of influence (Casier, 2021). The term balance of power may be misleading in this case because Russia has no interest in the engagement of foreign powers such as the EU or NATO (Delcour, 2018, p. 16). The latter has been declared a strategic threat because of its rotational deployment to the Baltic states and the strike capabilities. Further, NATO’s enhanced cooperation with Ukraine and Georgia has served as justification for Russia’s direct aggression during the war in Georgia in 2008 as well as the rather indirect support for pro-Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine. The EU is also seen as an actor in western hybrid warfare employing democracy promotion as a weapon (Duke & Gebhard, 2017, pp. 385–386; Nitoiu & Sus, 2019, p. 12). According to realist scholars such as Mearsheimer, a Russian response to the increased Western involvement in the region should not have come as a surprise (Mearsheimer, 2014). Secondly, geoeconomic factors need to be considered. The EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) further intensified the economic competition. In contrast to the ENP, which allowed for inclusive Russian cooperation, the EaP was perceived as exclusionary. The EaP encompasses an enhanced contractual framework of an Association Agreement including the establishment of a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) (Delcour, 2018, p. 23; Noutcheva, 2021). By nature, this leads to a clash of customs unions. This could be witnessed in Ukraine, which as a smaller country had to choose between two major powers. On the one hand, Ukraine depended on the EU’s market for its exports and would have benefited from the DCFTA. On the other hand, Ukraine also needed access to Russian market and energy, which would have been facilitated through membership in the EEU (Burlyuk & Shapovalova, 2017, p. 44). On a conceptual level, the zero-sum rational lead to escalation in Ukrainian which exemplifies an ‘integration dilemma’ (Duke & Gebhard, 2017, p. 383). While Russia had an economic interest in including Ukraine in the EEU, its action was most likely also connected to the general understanding of keeping Ukraine within its area of influence. Russia maintains strong ties to the Ukrainian energy sector and is highly dependent on its military base in Sevastopol, which hosts Russia’s Black Sea Fleet (Noutcheva, 2018, p. 321; Yuhas & Jalabi, 2014). Thirdly, Russia’s use of force fits the realist rationale as well. In 2008, Russia conducted an act of aggression and invaded Georgia by traditional military means. This proves the use of hard power politics (Cohen, 2018). In the case of Ukraine, Russian involvement was more subtle although it also included military support. Russia sent government consultants to Kyiv and provided anti-riot equipment to the Yanukovych government and continues to provide weapons to separatists in Eastern Ukraine up until today (Burlyuk & Shapovalova, 2017, p. 47).

Applying a realist approach to the assessment of Russian relations with the MENA region, the three main characteristics mentioned above structure the analysis as well. Firstly, Russian actions have been aimed at setting a new balance of power in the region by being an indispensable actor. Recognizing its decline after the Cold War, Russia took various steps to establish itself as a powerbroker in the region (Frolovskiy, 2019). The Syrian crisis almost led to the termination of the Assad regime, which was the only major Russian ally left in the region and provided the strategic port of Tartus (Casier, 2021). Therefore, it was crucial for Russia to stabilize the incumbent leadership. Recognizing the regional and international isolation after the annexation of Crimea 2014, the Russian pro-government intervention in Syria in fall of 2015 changed the international landscape (Dannreuther, 2019, p. 728). The US were resistant to engage militarily in the conflict because it lacked domestic support and also shifted its geopolitical priorities from MENA to Asia (Huber, 2015, p. 66). Taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the US, Russian leadership negotiated a deal to remove and destroy Syria’s chemical weapons (Fawcett, 2018, p. 72). Concerning Libya, Russia initially allowed for NATO intervention but immediately challenged that decision once NATO overstepped its mandate. Over the past years, Russia has slowly built up its presence in Libya through mercenaries and private military security contractors such as the Wagner Group (Arnold, 2020). This has turned Russia into a powerful actor in negotiations about pacifying and stabilizing the country. Further, Russia gained more power in the conflict in neighboring Egypt once the US failed to provide sufficient economic and military support to the post-Mubarak government. Since then, economic ties have been tightened through arms deals and Russia was also allowed to set up air bases (Dannreuther, 2019, p. 737). These three country examples highlight how Russia took advantage of local conflicts and the withdrawal of the US to maximize its power in the conflicts and beyond in the entire region. Apart from this, it needs to be pointed out that local Arab and non-Arab states alike welcomed Russia’s return to the region. Having multiple external powers interested in the region allows local actors the chance to manipulate external forces to their benefit (Dannreuther, 2019, p. 740). Secondly, Russia also pursues geoeconomic interests in the region. Being challenged by economic sanctions in response to the annexation of Crimea, the MENA region became more important as a trading partner. To diversify its economic activities, Russia has also developed economic ties with traditional pro-American countries. Turkey is a partner to build the so-called Turkish Stream gas pipeline and Israel has turned into an essential provider of technology to the Russian economy (Dannreuther, 2019, pp. 737–738). Thirdly, having presented the military intervention in Syria and the indirect support of armed forces in Libya above, Russia has employed traditional hard power means and demonstrated the use of force. However, within the broader region, Russia maintained a quite neutral position in other conflicts. It does neither actively participate in the Yemen civil war nor the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This is beneficial for Russia because it is flexible enough to fill a vacuum of power once the balance of power shifts (Dannreuther, 2019, p. 737; Ramani, 2020).

Concluding, the analysis of Russian activities in Eastern Europe and MENA has shown that the realist dimensions of balance of power, geoeconomic interests as well as use of force have a great explanatory power. Recognizing the heterogeneity within and among the regions, Russian action appears to be driven by a power-maximizing rationale going even beyond the region to become a global power again (Casier, 2021).

Russia’s impact on EU policy

Based on the analysis of Russian actions in the EU’s neighboring regions, it is important to investigate to what extent they constrain or enable the EU’s actions within the ENP in Eastern Europe and the MENA region. In general, comparing Russia’s and the EU’s approaches often resembles a clash of worldviews. While Russian actions are inherently based on a realist rationale, the EU seems to dismiss the concept of balance of power, geoeconomics and use of force by nature (Raik, 2019, pp. 57–63). Considering the case of Eastern Europe, on the one hand, Russia’s role in the Ukraine crisis has limited the EU’s motivation in openly engaging with its neighborhood by establishing economic relations as well as promoting its norms and values. It can be argued that this experience has shaped the thinking of EU officials such as the EU HR/VP Borrell who frequently speaks of the ‘language of power’ and promotes a more geopolitical EU (Borrell, 2019). The term ‘principled pragmatism’ also resembles that the EU tends to prioritize stability and resilience over democracy promotion (Juncos, 2017). On the other hand, the Ukrainian conflict has also reduced the trust in Russia as a partner in the region. Disregarding Ukraine’s sovereignty, violating its territorial integrity and breaking international law may convince actors to favor the EU policies instead of Russian relations (Raik, 2019, p. 56). It may also be argued that Russia actually contributed to Ukraine’s turn to the West because Ukraine eventually signed the DCFTA within the EaP and a majority of Ukrainians consider Russia an aggressor (Burlyuk & Shapovalova, 2017, p. 49; Noutcheva, 2018, p. 323). In the MENA region, the EU has been comparatively less involved than in Eastern Europe. However, individual member states have a long history of involvement. Unfortunately, they sometimes act in a contradictory manner e.g. when supporting opposing actors in Libya. This further complicates approaches to streamline a coherent EU policy (Fawcett, 2018, p. 78). Hence, Russian actions in the region do not substantially impact the EU, which is rather preoccupied with internal divisions. However, establishing relative stability in Syria has surely reduced migratory pressure on the EU.

Conclusion

In summary, I argue that Russia’s actions in Eastern Europe and the MENA in the past two decades can be explained with a realist approach. Reflecting upon Russian involvement in the two regions, on the one hand, Russia maintains institutionalized relations with some relatively loyal former Soviet countries such as Belarus. On the hand, the troubled relations with Georgia or Ukraine show the cleavages within the post-Soviet area. To the contrary, Russia maintains well-functioning and pragmatic working-relations with almost all MENA states including the close US ally Israel as well as its antagonist Iran. Applying a realist logic, I conclude that three main characteristics guide Russian actions in both regions. Firstly, Russia considers the balance of power as a zero-sum game. In its ‘near neighborhood’, it claims privileged interests and is critical of Western involvement in post-Soviet countries. In the MENA region, Russia has become an indispensable actor and fills the vacuum of power created by the US withdrawal from the region. Secondly, geoeconomic interests serves as an explanation. The clash of custom unions between the EU’s DCFTA and the EEU in Ukraine exemplifies how trade relations can facilitate conflicts. Further, the MENA region has become an important trading partner for Russia, whose economic power is limited by Western sanctions. Thirdly, Russia has also shown that it is not shy of using force in both regions. It employed hard power during the war in Georgia and provided military support to Ukrainian separatists or the Assad regime. Finally, considering an EU perspective, I argue that Russia’s hostile approach to Eastern Europe has constrained the EU’s liberal approach. It is at least rhetorically complemented by a realist understanding, which is expressed in the term ‘principled pragmatism’. However, Russia also deepened the cleavage among post-Soviet countries and has thereby indirectly supported the closer alignment of Ukraine and Georgia with the EU. Concerning the MENA region, the EU’s involvement has been limited and security oriented, which was arguably not significantly impacted by Russia although it stabilized the conflict in Syria which reduced migratory pressure on the EU.

Thank you for investing your time in reading this post. If you have feedback, questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to me on twitter.

References

References Arnold, T. D. (2020). Exploiting Chaos: Russia in Libya. https://www.csis.org/blogs/post-soviet-post/exploiting-chaos-russia-libya Borrell, J. (2019). Hearing with High Representative/Vice President-designate Josep Borrell. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190926IPR62260/hearing-with-high-representative-vice-president-designate-josep-borrell Burlyuk, O., & Shapovalova, N. (2017). “Veni, vidi, … vici?” EU performance and two faces of conditionality towards Ukraine. East European Politics, 33(1), 36–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2017.1280470 Casier, T. (2021). Russia and the neighbourhood. Cohen, A. (2018, August 10). The Russo-Georgian War’s lesson: Russia will strike again. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-russo-georgian-war-s-lesson-russia-will-strike-again/ Dannreuther, R. (2019). Understanding Russia’s return to the Middle East. International Politics, 56(6), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-018-0165-x Delcour, L. (2018). Dealing with the elephant in the room: the EU, its ‘Eastern neighbourhood’ and Russia. Contemporary Politics, 24(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1408169 Duke, S., & Gebhard, C. (2017). The EU and NATO’s dilemmas with Russia and the prospects for deconfliction. European Security, 26(3), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2017.1352577 Dunne, T., & Schmidt, B. C. (2020). 6. Realism. In J. Baylis, S. Smith, & P. Owens (Eds.), The globalization of world politics: An introduction to international relations (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordpoliticstrove.com/view/10.1093/hepl/9780198739852.001.0001/hepl-9780198739852-chapter-6 Fawcett, L. (2018). MENA and the EU: contrasting approaches to region, power and order in a shared neighbourhood. Contemporary Politics, 24(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1408172 Frolovskiy, D. (2019, February 1). What Putin Really Wants in Syria. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/01/what-putin-really-wants-in-syria-russia-assad-strategy-kremlin/ Huber, D. (2015). A Pragmatic Actor — The US Response to the Arab Uprisings. Journal of European Integration, 37(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.975989 Hyde-Price, A. (2006). ‘Normative’ power Europe: a realist critique. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500451634 Juncos, A. E. (2017). Resilience as the new EU foreign policy paradigm: a pragmatist turn? European Security, 26(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2016.1247809 Mearsheimer, J. J. (2014). Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Neoliberal Delusions That Provoked Putin. Foreign Affairs, 93(5), 77–89. Mearsheimer, J. J. (2017). 3. Structural Realism. In T. Dunne, M. Kurki, & M. Smith (Eds.), Politics Trove. International Relations Theories (pp. 51–67). Oxford University Press. Nitoiu, C., & Sus, M. (2019). Introduction: The Rise of Geopolitics in the EU’s Approach in its Eastern Neighbourhood. Geopolitics, 24(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1544396 Noutcheva, G. (2018). Whose legitimacy? The EU and Russia in contest for the eastern neighbourhood. Democratization, 25(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1363186 Noutcheva, G. (2021). EU Relations with the Eastern Neighbours: from ENP to the Eastern Partnership. Raik, K. (2019). The Ukraine Crisis as a Conflict over Europe’s Political, Economic and Security Order. Geopolitics, 24(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1414046 Ramani, S. (2020). The Russian Role in the Yemen Crisis. In S. W. Day & N. Brehony (Eds.), Global, regional, and local dynamics in the Yemen crisis (pp. 81–96). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35578-4_6 Rumer, E. B. (2019, October 31). Russia, the Indispensable Nation in the Middle East. Foreign Affairs Magazine. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2019-10-31/russia-indispensable-nation-middle-east Yuhas, A., & Jalabi, R. (2014, March 7). Ukraine crisis: why Russia sees Crimea as its naval stronghold. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/07/ukraine-russia-crimea-naval-base-tatars-explainer

Cover photo retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/rise-of-the-regional-hegemons-1432592429 .