#sofagate - The EU as a Normative Gender Actor - Leading by Example?

Gender Equality is one of the core values of the European Union (EU). It is part of the EU’s legal and political framework and the EU has a comprehensive track record as a gender equality promoter in its foreign policy (Beier & Çağlar, 2020, p. 426). Starting with its development policy, neighborhood, trade, security, and defense policies have followed suit to various degrees. Focusing on the EU as a gender actor, the EU employs its normative power to teach others on gender issues. However, when looking at the results, it lacks a systematic practice of what it preaches leading to various contradictions (Debusscher & Manners, 2020; J. V. D. Vleuten, 2017).

These range from conflicting measures in different policy fields to failures in leading by example. The former has been addressed in numerous contributions to the literature. For example, Hoijtink & Muehlenhoff investigated the interplay of the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and migration as well as development policy by showing how normalizing military power and military masculinities beyond the CSDP threatens gender-sensitive measures (Hoijtink & Muehlenhoff, 2020). In addition, contradictions also arise when trade liberalization clashes with development policies to empower local female farmers. Liberalization usually has disproportionate effects on women who in comparison to men tend to have less resources and power (ACDIC et al., 2007; Debusscher & Manners, 2020, p. 416).

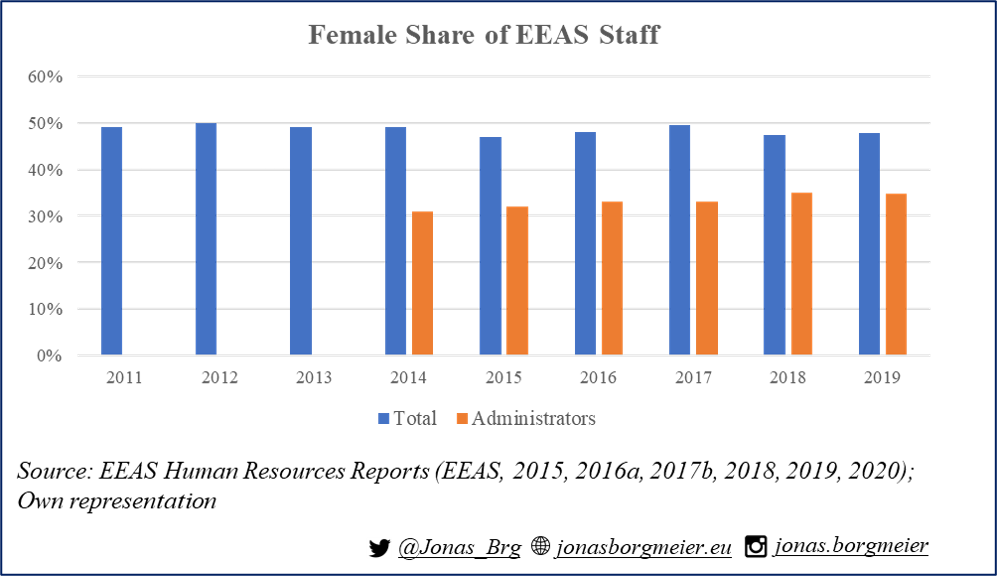

The latter aspect, leading by example, also concerns the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as a whole. Failures to lead by example are exemplified by the fact that the EU lacks a gender equal representation. While the European External Action Service (EEAS) as the EU’s main foreign policy institution is tasked with promoting gender equality, its own organizational structure is dominated by male decision makers. In 2019, men made up 65% of all the administrators, having an even bigger share of 80% with regard to top level positions (EEAS, 2020). The lack of women’s representation undermines the EU’s role as a leader by example and a credible international actor in general. Overall, Guerrina & Wright contend that the EU is not (yet) a normative gender power in external relations (Guerrina & Wright, 2016, p. 311). Building upon this, the literature lacks an account of how the EU has worked towards becoming a “more” normative gender actor.

Contrasting the EU’s self-proclaimed role as a frontrunner in promoting gender equality and the lack of women in decision making position, in this blog post I investigate whether there has been a development towards more inclusion of women in institutional structures in the past decade (EEAS, 2020; High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2020a). In other words, I explore how the evolution of the EU discourse on gender promotion in its foreign policy correlates with the development in gender equal representation. I intend to fill the gap in the literature by offering an inward-looking analysis of the EEAS as a representative of the EU’s CFSP in the world.

Firstly, a literature review briefly presents the scholarly discourse on the EU as a normative power and how it has been applied to the field of gender equality. Further, major developments of the EU becoming a gender equality promoter internally as well as externally are introduced.

Secondly, an analytical framework applies the concept of normative power Europe to the field of gender equality promotion in the EU’s external relations. It recognizes the EU’s normative understanding as a front-runner for advancing gender equality (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2020a). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the EU has continuously promoted and expanded the scope of gender equality in its discourse as well as that it has increased the share of women’s representation to adhere to its core value of gender equality.

Thirdly, on the one hand, the primary data analysis assesses key documents on gender equality. On the other hand, data on female representation in the EEAS in the past decade is used as an indicator to assess whether the EU has come closer to live up to its standards to be a credible leader by example.

Finally, the results are contextualized and evaluated before drawing conclusions about whether and if so, to what extent the EU improved female representation in its main CFSP institution.

Literature Review

The debate on the EU as a normative power can be traced back to Ian Manners’ seminal work published in 2002. He proclaimed that the EU’s power as an international actor derives from its identity and its ability to project core values in outward-facing policies. Employing core foundational norms and values as base for policy formulation and projecting these in its foreign and security policy is central to the EU’s role as a normative actor in the international arena (Manners, 2002).

Although Manners’ idea was extensively criticized (Diez, 2004; Hyde-Price, 2006; Noutcheva, 2009), his normative power approach was used to engage with the EU as a gender actor. A normative power approach focuses explicitly on questions such as whether, what and how should the EU advance gender equality in its external relations (Debusscher & Manners, 2020). Various scholars applied these normative lenses when investigating the rationale of gender mainstreaming in the EU discourse (David & Guerrina, 2013) or with regard to the development policy (Debusscher, 2011).

More recently, Debusscher & Manners pointed out that it needs a rethinking of the EU as global gender actor considering a holistic intersectional and inclusive approach of “gender+” (Debusscher & Manners, 2020). In this blog post I refer, in particular, to Guerrina & Wright who reflected upon the EU’s role in promoting the UN ‘women, peace and security’ (WPS) agenda and came to the conclusion that the EU is not (yet) a normative gender power in external relations (Guerrina & Wright, 2016, p. 311). Building upon their assessment, this work aims to fill the literature gap on how the EU has addressed the issue.

Before developing an analytical framework for the investigation, it is important to consider the EU’s track record as a gender equality actor. Historically, the EU institutions started promoting gender equality internally before expanding beyond its member states. Already in 1957, gender equality was introduced in the Treaty of Rome. Article 119 included the principle of equal pay for male and female workers. It ensured that lower wages for women would not lead to unfair competition. This economic justification illustrates the rationale behind granting women’s rights at that time.

Gender equality was not seen as an end in itself, but rather as a means to achieve a level playing field for competition (Jacquot, 2015). This neoliberal motivation has shaped the EU’s understanding of gender equality substantially. For instance, in the 1980s, “positive” measures to train women and to introduce a more family-friendly work environment were actually intended to attract more women into the workforce to increase economic growth (Weiner & MacRae, 2014, p. 4).

However, in 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam defined gender mainstreaming as a core principle obliging all European institutions to encompass gender dimensions in their policy areas. Gender equality was now defined as a substantive goal making its promotion essential in all measures. A transformed understanding of gender as an end in itself led to its inclusion in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (Weiner & MacRae, 2014, p. 5). However, different motivations for and diverging understandings of gender equality and significant differences between member states persist up until today.

Having reviewed the internal dimensions, the principle of gender mainstreaming also increased the EU’s efforts in external relations. The EU incorporates gender aspects in a variety of its foreign policies. It includes gender equality in the enlargement and neighborhood policy which is monitored by the European Institute for Gender Equality. Further, the EU puts efforts in mainstreaming gender in its civilian missions and also considers the issue in its trade policy. For instance, the modernization of the EU-Chile Association Agreement entails a gender impact assessment as well as an entire chapter devoted to gender equality (European Commission, 2021; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019, p. 62).

Many of the EU’s activities are guided by the UN ‘women, peace and security’ agenda, which was established by the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1325. It was the first time that the Security Council discussed women and the disproportionate impact on them in conflicts (Guerrina et al., 2018, p. 1044). Among others, the resolution also highlights the importance of women’s representation and equal participation to maintain and promote peace and security (United Nations Security Council, 2000).

The EU developed a comprehensive approach to implement the resolution in 2008, which sets targets to include more women mediators and negotiators as well as civil society groups in peace negotiations. Co-operations with the United Nations, NATO and other multilateral organizations are central in the EU’s engagement.

In 2015, the EU’s efforts were institutionalized by the creation of the post of EU/EEAS Principal Advisor on Gender within the EEAS (European Commission, 2021; Lazarou & Zamfir, 2021, p. 6). According to former High Representative and Vice-President of the Commission (HR/VP) Federica Mogherini, the advisor was to coordinate the EEAS’s work on gender equality and women’s empowerment, and on WPS as well as to promote accountability and to ensure internal and external coherence. Unsurprisingly, this broad mandate was criticized for being unclear. Further, the post was not sufficiently funded considering that a small staff of two and a seconded expert, constrained by limited financial resources was to fulfill this complex mandate (Horst, 2016). A year later, the EU Global Strategy (EUGS) defined gender equality as crucial to develop an integrated approach to conflicts and crises. With regard to conflict settlement, it builds on implementing the UNSC Resolution 1325 and improving the EU’s internal gender balance (EEAS, 2016b, p. 31).

Since 2010, the EU has developed three five-year Gender Action Plans (GAP) to improve the implementation of gender mainstreaming in its external relations. The most recent one was published in November 2020.

Analytical Framework

Building upon Manners’ normative power approach and considering the EU’s track record presented above, an analytical approach is developed. Drawing from the EU’s efforts of implementing gender mainstreaming in all its policy areas since the Amsterdam Treaty in 1997, a normative understanding of the EU as a gender actor can be assumed. This is substantiated by official statements considering gender equality promotion a part of the EU’s DNA (European Commission, 2015). Further, the most recent GAP clearly defines the EU as a global front-runner in promoting gender equality in its external actions (European Commission, 2020).

Contrasting this self-perception as a gender actor with the scholarly assessment that the EU has not (yet) become a normative gender power in external relations, it can be assumed that the EU has taken steps as well as made progress towards fulfilling its role as a leader by example (Guerrina & Wright, 2016, p. 311).

This work takes a two-tier approach to assess this in different dimensions. On the one hand, it regards the discourse on gender equality within the EU. Considering the presented failure to lead by example in terms of female representation, it can be expected that the issue has been continuously addressed in official documents and statements. Therefore, the first hypothesis assumes that:

H1: The EU has continuously addressed the lack of women in its institutional representation in its official documents.

On the other hand, the development of the share of female staff in the EEAS will be subject to analysis. Taking closer look at the EEAS, it is one of the key institutions in managing the EU’s external relations. It is headed by the HR/VP and incorporates a network of 139 delegations and offices worldwide. Based on the EU’s normative understanding as a credible promoter of gender equality and leader by example, it can be assumed that the EEAS has continuously increased the share of women in its staff including management positions.

H2: The share of female staff has continuously increased on all levels of employment.

Finally, it can be presumed that both dimensions correlate positively because discourse has the power to affect actions. According to Foucault, discourse is constitutive of reality (Foucault & Hurley, 1998, p. 100). Consequently, it can be theorized that this would lead to an increase of female staff.

H3: The gender discourse on equal representation correlates positively with the share of female staff.

Structuring the analysis, H1 and H2 are addressed individually by investigating primary sources. Firstly, a content analysis of official documents is conducted to find out whether, and if so how, the share of female representation in European institutions is addressed. Secondly, a data analysis scrutinizes the characteristics of staff working in the EEAS over the past decade. Subsequently, the results of the analyses provide the ground to assess H3.

Analysis

Based on the analytical framework developed above, the forthcoming chapter encompasses the assessment of the three hypotheses. They are addressed individually by providing the research results.

H1: The EU has continuously addressed the lack of women in its institutional representation in its official documents.

To address H1, this work analyzes the content of official documents and statements of the past ten years investigating whether, and if so, how they address the lack of female representation in EU staff. The three GAPs, more specifically the respective joint staff working documents, serve as key documents because they are intended to improve the implementation of gender mainstreaming in the EU’s external relations. The first Gender Action Plan (GAP I) was published in 2010. It addressed a five-year time period, being followed by Gender Action Plan II (GAP II) which covered the following five years. The most recent Gender Action Plan III (GAP III) was published in November 2020 and is applied to the next years to come (Beier & Çağlar, 2020, p. 426).

The GAP I mostly focuses on gender equality and women’s empowerment with regard to development. It is based on a three-pronged approach encompassing political and policy dialogue, gender mainstreaming as well as specific actions. While it recognizes that women are under-represented in government and decision-making bodies, it does not seem to address the situation within EU bodies. Consequently, the operational framework of GAP I does not contain objectives to improve women’s representation. The second objective to build an in-house capacity on gender equality in development is the only indication that the EU takes an inward-looking approach (European Commission, 2010).

The GAP II has a bigger scope promoting gender equality measures in all areas of the EU’s external relations. These range from CFSP and Common Commercial Policy to Area of Freedom, Security and Justice including immigration and asylum. This is presented as the basis for achieving the EU’s objective of stopping violence against women and girls, guaranteeing their socioeconomic rights as well as their representation and participation (European Commission, 2021). The GAP II also pushes for an institutional culture shift making it more effective in delivering results. Commitments are to be translated into clear and tangible results based on better coordination, coherence, leadership and analysis (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2015, p. 13).

Beier & Çağlar describe the GAP II as ambitious going beyond political and institutional reach to demonstrate the EU’s global leadership role in gender equality (Beier & Çağlar, 2020, p. 427). This underlines the EU’s perception of being at the forefront of the protection and fulfilment of girls’ and women’s rights. However, as already being witnessed in the GAP I, the unequal representation in EU institutions is not addressed. Whereas the documents state that strengthening women’s voice and participation at all levels of society can have significant positive impacts, it does not consider the internal dimension of the EU’s shortcomings as a leader by example (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2015, pp. 2–5).

The latest GAP III reiterates the EU’s role as a global front-runner in promoting gender equality. It provides a three-pronged approach encompassing gender mainstreaming, targeted actions, and political dialogue (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2020a, p. 2). The GAP III defines five pillars.

Firstly, a cross-cutting priority improves gender mainstreaming in all external policies and sectors. This entails a gender-transformative, rights-based, and intersectional approach. A gender transformative approach aims the change the gender-power balance for a positive change, preventing existing structures to reproduce discrimination and inequalities. Intersectionality acknowledges multiple characteristics and identities creating individualized and unique positions of inequality. The concept of intersectionality was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the context of Black women being discriminated against which was not solely based on their gender but also due to their racial belonging (Crenshaw, 1991, p. 1244; Debusscher, 2021).

Secondly, the GAP III proposes a multi-level approach fostering strategic EU engagement at multilateral, regional and country level with various partners. Thirdly, key priorities are set including the prevention of gender-based violence or the advancement of equal participation and leadership.

Fourthly, the GAP III highlights the EU’s role to lead by example. It aims for a gender-responsive and gender-balanced leadership at top EU political and management levels. To achieve this, investments in training, knowledge and pooling actions with member states are needed.

Finally, the reporting and communicating the results is seen as a crucial pillar to increase public accountability, show transparency and allow access to information (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2020a).

The fourth pillar eventually addressed the internal dimension which had been missing in the previous GAPs. This is translated into objective 10 aiming for an enhanced gender-responsive leadership. It means that a gender balanced management needs to be achieved in the EEAS headquarters, external Commission Services, EU delegations as well as CSDP missions and operations (High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 2020b, pp. 5–6).

In addition to the GAPs as key documents, this research also considers the EUGS, which was published in 2016. While it does not address internal gender imbalances as a main issue, it refers to improving the EU’s internal gender balance in a sub-sentence in the chapter on conflict settlement (EEAS, 2016b, p. 31). A year later, the EEAS also introduced the EEAS Gender and Equal Opportunities Strategy (GEOS). It was developed by the Task Force on Gender and Equal Opportunities and proposed a structured and inclusive process to promote gender equality as one of their three main priorities. Therefore, they suggested the appointment of an Equal Opportunities Officer. The GEOS recognizes the importance of the GAP II initiating a culture shift but argues that it does not substitute a stand-alone strategy focused on the EEAS. The GEOS shows that middle and high-level management positions have a male dominance of 75% and 87% and openly criticizes the overall gender distribution as well as the fact that has stagnated in the past years. To address this issue, the strategy announces that specific targets will be set and a talent management will be implemented but remains unclear about the details (EEAS, 2017a, pp. 7–8).

In summary, the analysis of the GAPs has shown that the need to address the internal gender imbalances was only included in the latest version. However, it is worth pointing out that it defines specific targets to achieve gender balance also in management positions. Further, it needs to be considered that a general culture shift was announced in the GAP II 2015, awareness for the internal gender balance could be found in the EUGS in 2016 and was openly addressed in the GEOS in 2017.

Consequently, in response to H1, it can be stated the EU may not have continuously addressed the issue but did so increasingly in the past years.

H2: The share of female staff has continuously increased on all levels of employment.

Acknowledging the increased discourse on gender imbalance, it is worth investigating the empirical data. Based on the annual human resources reports, the development of female representation in the EEAS as whole and with regard to management positions as “administrators” is analyzed.

The figure below shows the share of female employees in the EEAS since its establishment in 2011. It is noticeable that gender distribution among all the staff is almost balanced throughout the years. In 2019, 48% of 4,474 people working in the EEAS, whether directly employed or through external contractors, were women (EEAS, 2020, p. 39). Whereas this number does not suggest an gender imbalance in representation, it is important to have assess how gender representation is spread across different hierarchical positions. The comparison between assistants and administrators serves as an example. On average, about two thirds of assistants are female, while the opposite is true for the administrators.

The figure also illustrates the share of women in administering positions since 2014. It can be seen there has only been a slight increase from 31% to 35% over the past five years. In addition, making the gender distribution among different administrator grades more transparent offers additional insights.

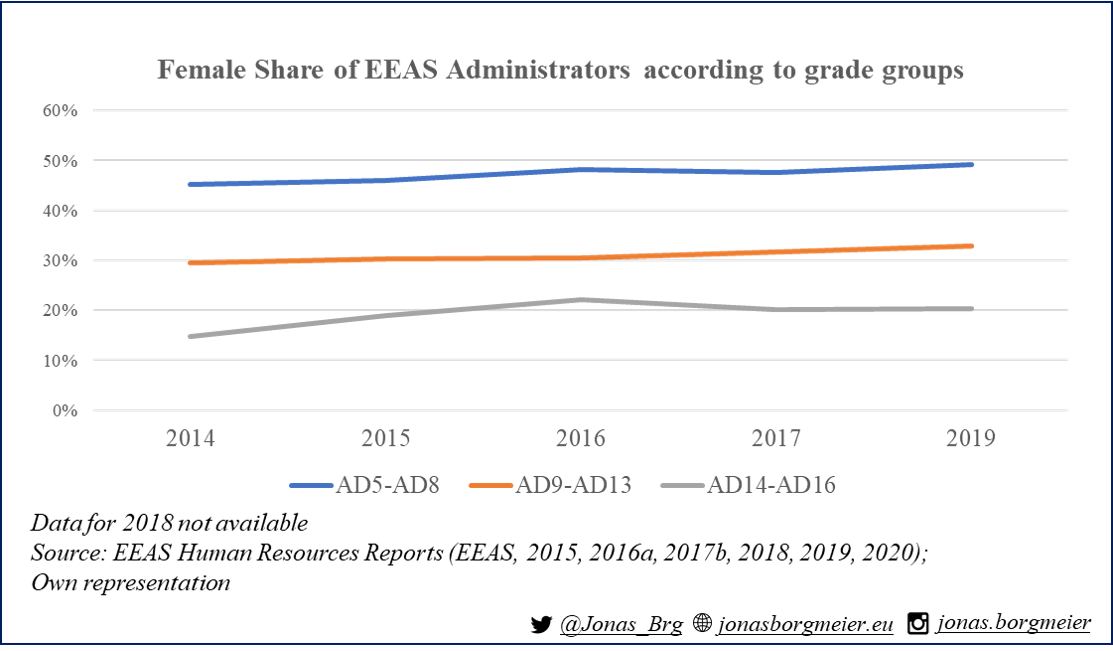

The next figure shows that the gender balance among the lower ranking positions is almost achieved. However, the share of women decreases substantially when assessing the medium- and high-level positions. Considering the trend of the past years, the divide between the different grade groups has generally persisted. However, all of them have slowly increased the female share by single-digit percentage points.

Regarding H2, it is noticeable that there is a general divide of female representation between the overall staff and administrator positions, as well as between low-level and higher-level administrators. Overall, a slight, but continuous, increase of female representation can be witnessed.

H3: The gender discourse on equal representation correlates positively with the share of female staff.

Finally, having analyzed the discourse and empirical data, it is explored how these two dimensions correlate. While the normative aspiration of the EU as a gender actor has developed in the past decades, the assessment of H1 has shown that, for a long time, internal gender balance was not part of the discourse in official documents. This arguably increased in the past five years.

In comparison to this, the actual gender representation with the EEAS staff remained relatively stable. However, slight increases could be witnessed. Therefore, it may be stated that H3 is true in that sense that it describes a general trend towards more gender equality within EU institutions – in the discourse as well as in the share of female administrator positions. However, considering the limited data and the weak degree of correlation, claiming a causal relationship appears to be rather speculative.

Conclusion

Building upon the notion that the EU is not (yet) a normative gender power in external relations (Guerrina & Wright, 2016, p. 311), I investigated the question whether and if so, to what extent the EU is working towards becoming one. I focused on the fact the EU fails to lead by example in female representation in decision making positions. Hence, the discourse on as well as the empirical development of gender balance within EU institutions was assessed. Based on the conceptualization of the EU as a normative power in gender equality promotion, an analytical framework was established to develop three hypotheses about the EU’s efforts to live up to its own standards.

Firstly, it was assumed that the EU has continuously addressed the lack of women in official documents. The analysis of key documents such as the Gender Action Plans has shown that the issue was not raised continuously because it was only included in recent years. However, there are indications that the topic is increasingly and more comprehensively addressed.

Secondly, it was hypothesized that the share of female staff has continuously increased on all levels of employment. The assessment of human resources reports of the EEAS in the past ten years has shown that there is a general divide of female representation between the overall staff and administrator positions, as well as between low-level and higher-level administrators. In general, there has been a continuous increase of female representation across all administration levels although it has been quite slow.

Thirdly, it was assumed that the gender discourse on equal representation would correlate positively with the share of female staff. Based on the presented analyses, it can be concluded that there have been improvements with regard to gender equality in both dimensions.

Consequently, a positive correlation could be witnessed in recent years. However, this should not be mistaken as a claim of causation. The limited scope of this research does not offer enough evidence showing a causal link. Presenting these findings may initiate future research on the topic. An expanded discourse analysis as well as a more comprehensive empirical analysis may serve as foundation to further investigate the steps taken by the EU to eventually become a normative gender power in external relations.

In my opinion, a credible global gender actor needs to lead by example. The analysis has shown that there is still a lot of room for improvement. Consequently, EU officials should go beyond talking the walk and continue walking the talk. #sofagate has clearly shown that symbols play an important role in the EU’s internal as well as external perception. While we can hope, that next time there will be a chair for the female Commission President, it needs to be ensured that women and other marginalized groups are represented at the negotiation tables on all levels. Hence, a true representation includes meaningful participation and active influence in the decision making processes.

Thank you for investing your time in reading this post. If you have feedback, questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to me on twitter.

References

ACDIC, ICCO, Aprodev, & EED (Eds.). (2007). No more chicken, please: How strong grassroots movement in Cameroon is successfully resisting damaging chicken imports from Europe, which are ruining small farmers all over West Africa. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/3825757/no-more-chicken-please-aprodev

Beier, F., & Çağlar, G. (2020). Depoliticising Gender Equality in Turbulent Times: The Case of the European Gender Action Plan for External Relations. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 426–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920929886

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039 David, M., & Guerrina, R. (2013). Gender and European external relations: Dominant discourses and unintended consequences of gender mainstreaming. Women’s Studies International Forum, 39, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2012.06.005

Debusscher, P. (2011). Mainstreaming gender in European Commission development policy: Conservative Europeanness? Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2010.10.001

Debusscher, P. (2021). Development policy. In G. Abels (Ed.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge handbook of gender and EU politics (pp. 290–302). Routledge.

Debusscher, P., & Manners, I. (2020). Understanding the European Union as a Global Gender Actor: The Holistic Intersectional and Inclusive Study of Gender+ in External Actions. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919899345

Diez, T. (2004). Constructing the Self and Changing Others: Reconsidering `Normative Power Europe'. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 33(3), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298050330031701

EEAS. (2015). EEAS Human Resources Report 2014. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/hr_report_2014_final_en.pdf

EEAS. (2016a). EEAS Human Resources Report 2015. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eeas_human_resources_report_2015.pdf

EEAS. (2016b). Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe: A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf

EEAS. (2017a). The EEAS Gender and Equal Opportunities Strategy 2018-2023. https://eurotradeunion.eu/documents/WGgender.pdf

EEAS. (2017b). EEAS Human Resources: Annual Report 2016. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eeas_human_resources_reports_2016.pdf

EEAS. (2018). Human Resources: Annual Report 2017. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2018_05_15_hr_report_2017_final.pdf

EEAS. (2019). Human Resources Report 2018. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eeas_human_resources_report_2018.pdf

EEAS. (2020). Human Resources Report 2019. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eeas_human_resources_report_2019.pdf

European Commission. (2010). EU Plan of Action on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Development 2010-2015: Commission Staff Working Document. https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/public-gender/documents/eu-plan-action-gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment-development-2010-2015

European Commission. (2015). International Women’s Day [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_15_4573

European Commission. (2020, November 25). Gender Action Plan III – a priority of EU external action [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2184

European Commission. (2021). Promoting gender equality & women’s rights beyond the EU. https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/promoting-gender-equality-womens-rights-beyond-eu_en#eus-external-relations

Foucault, M., & Hurley, R. (1998). The will to knowledge [Amended reprint]. The history of sexuality: v. 1. Penguin Books.

Guerrina, R., Chappell, L., & Wright, K. A.M. (2018). Transforming CSDP? Feminist Triangles and Gender Regimes. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(5), 1036–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12705

Guerrina, R., & Wright, K. A.M. (2016). Gendering normative power Europe: lessons of the Women, Peace and Security agenda. International Affairs, 92(2), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12555

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. (2015). Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Transforming the Lives of Girls and Women through EU External Relations 2016-2020: Joint Staff Working Document.

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. (2020a). EU Gender Action Plan (GAP) III - An ambitious agenda for gender equality and women’s empowerment in EU external action: Joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020JC0017&from=EN

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. (2020b). Objectives and Indicators to frame the implementation of the Gender Action Plan III: Joint Staff Working Document. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/swd_2020_284_en_final.pdf

Hoijtink, M., & Muehlenhoff, H. L. (2020). The European Union as a Masculine Military Power: European Union Security and Defence Policy in ‘Times of Crisis’. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919884876

Horst, C. (2016). Why EU diplomacy needs more women. https://euobserver.com/opinion/133583

Hyde-Price, A. (2006). ‘Normative’ power Europe: a realist critique. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500451634

J. V. D. Vleuten (2017). The Merchant and the Message: Hard Conditions, Soft Power and Empty Vessels as Regards Gender in EU External Relations. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Merchant-and-the-Message%3A-Hard-Conditions%2C-Soft-Vleuten/a890486cd4389d89944d5eae73c5b212a0dea14a

Jacquot, S. (2015). Transformations in EU Gender Equality: From emergence to dismantling. Gender and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=4000943

Lazarou, E., & Zamfir, I. (2021). Women in foreign affairs and international security: Still far from gender equality.

Manners, I. (2002). Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00353

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019). Handbook Sweden’s feminist foreign policy. https://www.government.se/4ae557/contentassets/fc115607a4ad4bca913cd8d11c2339dc/handbook---swedens-feminist-foreign-policy.pdf

Noutcheva, G. (2009). Fake, partial and imposed compliance: the limits of the EU’s normative power in the Western Balkans. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(7), 1065–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903226872

United Nations Security Council (Ed.). (2000). Resolution 1325. https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1325(2000)

Weiner, E., & MacRae, H. (2014). The persistent invisibility of gender in EU policy: Introduction. In E. Weiner & H. MacRae (Eds.), The persistent invisibility of gender in EU policy (18th ed., pp. 1–20).

Thank you for providing the cover photo @AFP