A Feminist Foreign Policy for the EU?

Analyzing contemporary foreign policy, more and more countries label their foreign policy as “feminist”. Starting with Sweden, its Foreign Minister Margot Wallström announced her government’s feminist foreign policy in 2014 (Rothschild, 2014). Canada, France and Mexico have also been prominent states that employ feminism to describe the nature of their initiatives and actions in the global arena (Bigio & Vogelstein, 2020). In addition, there have also been discussions and concepts to develop a feminist foreign policy (FFP) for the European Union and the European Parliament even called on member states to adopt a feminist foreign and security policy (Bernading & Lunz, 2020; Neumann, 2020). In this blog post I present the principles and ideas of how to implement a feminist foreign policy in the European Union.

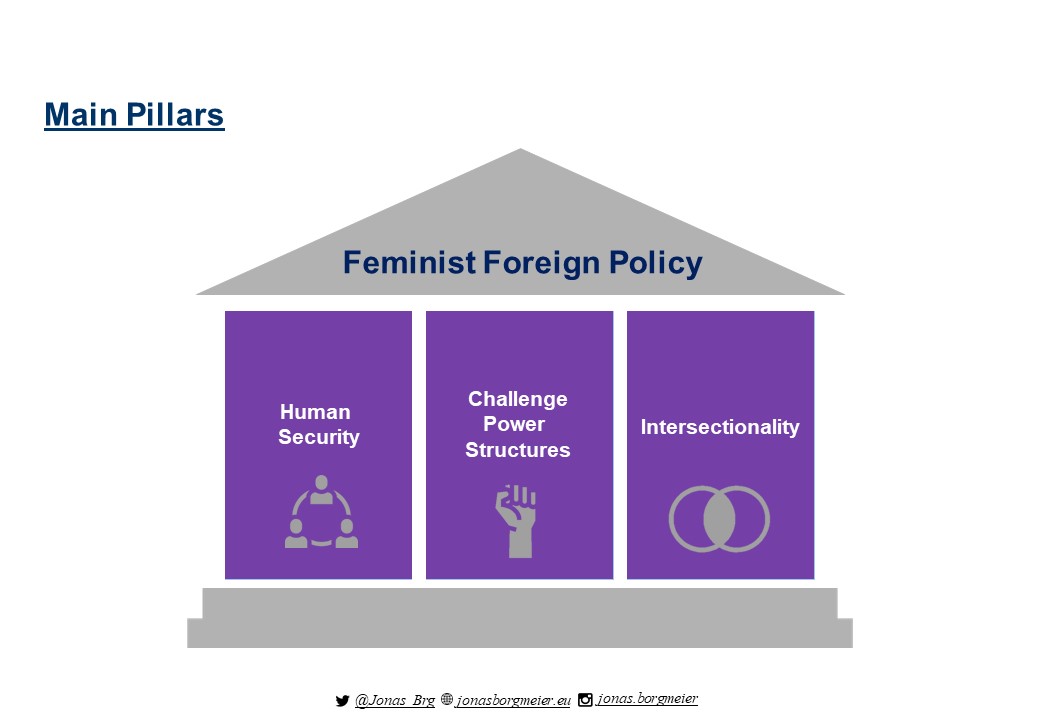

While there are various conceptualizations of how to define a feminist foreign policy, I argue that it is possible to distinct three main pillars. Firstly, a FFP goes beyond the traditional understanding of state security. Security is more than the absence of inter-state war. Employing feminist lenses, security allows the individual to enjoy safety and opportunities to develop personally. Secondly, a FFP challenges existing power structures that cause discrimination, opporession and violations of human rights. Most prominently, the global patriarchal system that systematically disadvantages women and other marginalized groups is the target of the second pillar. Thirdly, a FFP takes an intersectional approach. Intersectionality acknowledges multiple characteristics and identities creating individualized and unique positions of inequality. The concept of intersectionality was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the context of Black women being discriminated against which was not solely based on their gender but also due to their racial belonging (Crenshaw, 1991, p. 1244; Debusscher, 2021).

Critiques often contest the feasibility and utopian nature of a FFP. It is argued that states' policies have become more hostile and that the global arena is dominated by male leaders especially in the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China). It is questioned how a FFP can be applied to the realm of realpolitik. Translating a FFP into action appears to be the overarching challenge.

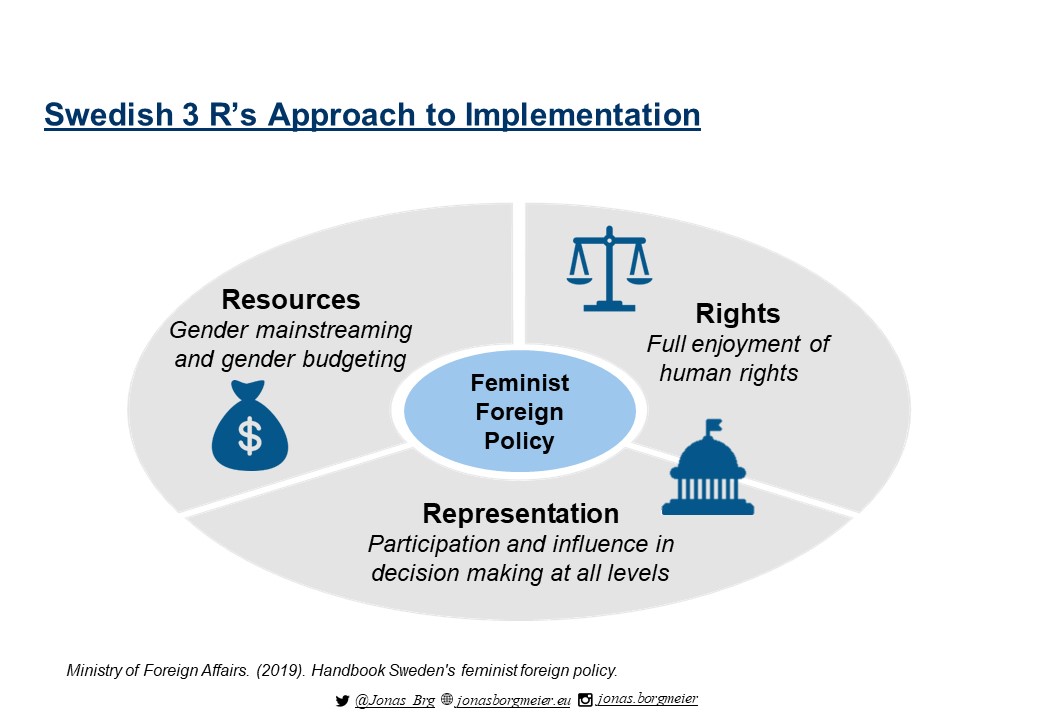

In response, Sweden developed a 3 R’s approach to implementation. It identifies rights, representation and resources as key areas to establish a feminist foreign policy. Rights encompass the full enjoyment of human rights for all individuals. The fact that women’s rights are human rights is highlighted in particular. Representation is seen as crucial to develop policies that empower women. Considering that diversity in decision-making improves the outcome for all, it needs to be stressed that the mere representation is not sufficient. Representation must ensure that women take part in decision making at all levels and that their needs are heard and taken seriously. Sufficient resources must be provided to finance gender equality initiatives. However, it is arguably more important to mainstream gender in all policy fields and to apply gender budgeting. This ensures that all measures are reviewed with respect to their effect on gender equality.

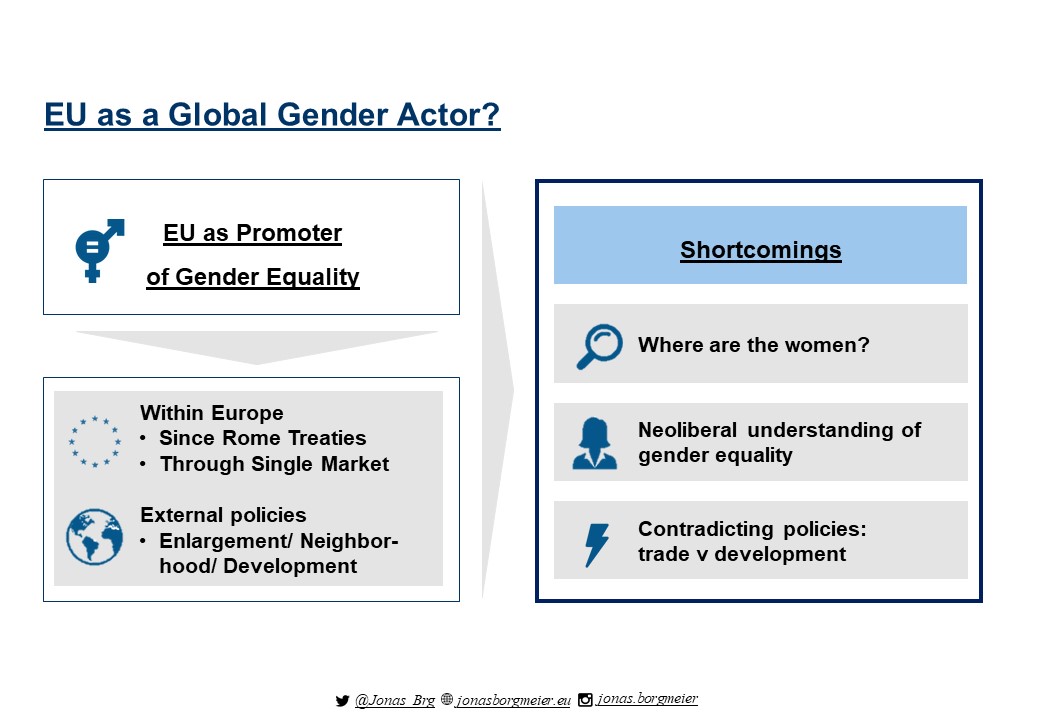

Based on the Swedish example, it may be wondered why and how a FFP is relevant for the European Union. So far, the EU has been an active promoter of equality. Gender equality is one of the core values of the European Union. It is part of the EU’s legal and political framework and the EU has a comprehensive track record as a gender equality promoter in its foreign policy (Beier & Çağlar, 2020, p. 426). Starting with its development policy, neighborhood, trade, security, and defense policies have followed suit to various degrees. Focusing on the EU as a gender actor, the EU employs its normative power to teach others on gender issues.

However, when looking at the results, it lacks a systematic practice of what it preaches leading to various contradictions (Debusscher & Manners, 2020; J. V. D. Vleuten, 2017). These range from conflicting measures in different policy fields to failures in leading by example. The former has been addressed in numerous contributions to the literature. For example, Hoijtink & Muehlenhoff investigated the interplay of the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and migration as well as development policy by showing how normalizing military power and military masculinities beyond the CSDP threatens gender-sensitive measures (Hoijtink & Muehlenhoff, 2020). In addition, contradictions also arise when trade liberalization clashes with development policies to empower local female farmers. Liberalization usually has disproportionate effects on women who in comparison to men tend to have less resources and power (ACDIC et al., 2007; Debusscher & Manners, 2020, p. 416). The latter aspect, leading by example, also concerns the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as a whole. Failures to lead by example are exemplified by the fact that the EU lacks a gender equal representation. While the European External Action Service (EEAS) as the EU’s main foreign policy institution is tasked with promoting gender equality, its own organizational structure is dominated by male decision makers. In 2019, men made up 65% of all the administrators, having an even bigger share of 80% with regard to top level positions (EEAS, 2020). The lack of women’s representation undermines the EU’s role as a leader by example and a credible international actor in general.

Further, the EU’s understanding of gender equality has been shaped by a neoliberal understanding. Gender equality was initially seen in the context of competition ensuring for a level playing field across the common market. In other words, gender equality was not seen as an end in itself, but rather as a means to foster economic growth and competition (Jacquot, 2015). While gender equality is nowadays part of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, different motivations for and diverging understandings of gender equality and significant differences between member states still persist.

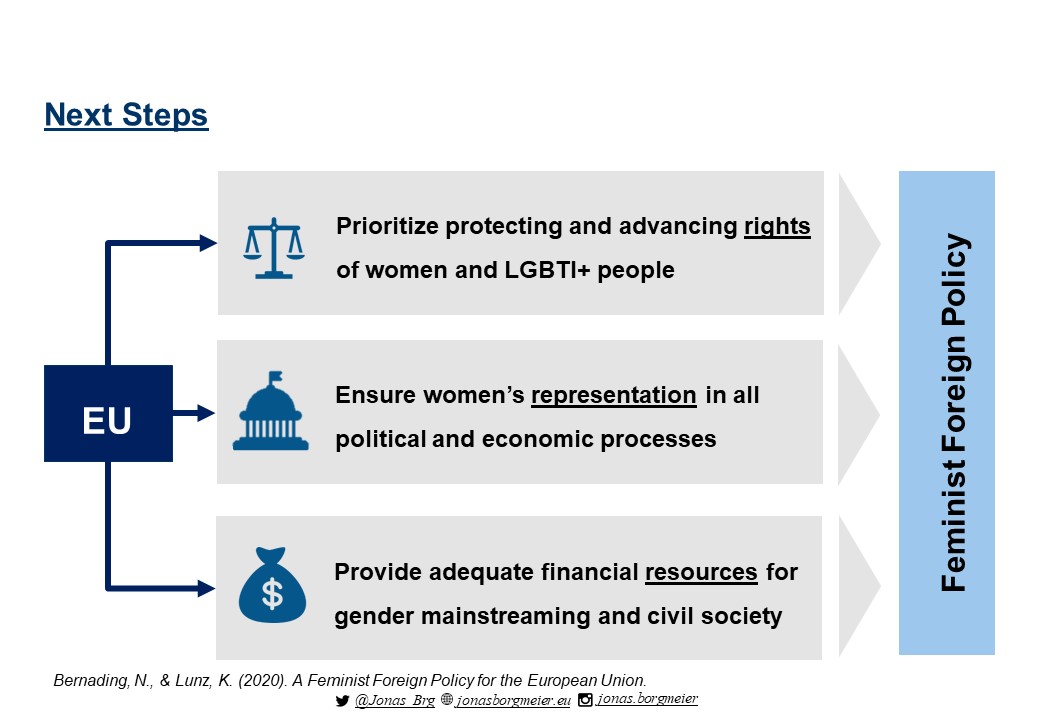

A FFP for the EU could combine the identified three pillars of human security, challenging power structures as well as intersectionality with the Swedish 3 R’s approach. Translating this into action, the following nexts steps are developed.

Firstly, a EU FFP prioritizes the protection of rights of women, LGBTI+ people and other marginalized groups. For example, this implies that the EU openly criticizes Turkey for leaving the Istanbul Convention. Secondly, women’s representation as well as the active participation in decision making processes is ensured across all policy areas and across all hierarchical levels. This addressed the role of the EU as a leader by example by also working towards gender parity in its own institutions such as the EEAS. Thirdly, adequate financial resources for gender equality promotion and a cross-cutting gender budgeting needs to be implemented. This also includes the provision of resources for civil society groups fighting for more gender equality within the EU and beyond.

In my opinion, a FFP for the EU offers the opportunity to develop the EU as a true and credible global gender actor. Acknowledging the transforming nature of a FFP, it may not be possible to implement it overnight. However, by applying its key principles and questioning existing policies out of a feminist perspective, small or even bigger steps can continiously be taken towards an EU FFP.

Thank you for investing your time in reading this post. If you have feedback, questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to me on twitter.

References

ACDIC, ICCO, Aprodev, & EED (Eds.). (2007). No more chicken, please: How strong grassroots movement in Cameroon is successfully resisting damaging chicken imports from Europe, which are ruining small farmers all over West Africa. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/3825757/no-more-chicken-please-aprodev

Beier, F., & Çağlar, G. (2020). Depoliticising Gender Equality in Turbulent Times: The Case of the European Gender Action Plan for External Relations. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 426–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920929886

Bernading, N., & Lunz, K. (2020). A Feminist Foreign Policy for the European Union. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57cd7cd9d482e9784e4ccc34/t/5ef48af0dbe71d7968ded22b/1593084682210/Feminist+Foreign+Policy+for+the+European+Union+-+Centre+for+Feminist+Foreign+Policy.pdf

Bigio, J., & Vogelstein, R. (2020). Understanding Gender Equality in Foreign Policy. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/report/understanding-gender-equality-foreign-policy

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Debusscher, P. (2021). Development policy. In G. Abels (Ed.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge handbook of gender and EU politics (pp. 290–302). Routledge.

Debusscher, P., & Manners, I. (2020). Understanding the European Union as a Global Gender Actor: The Holistic Intersectional and Inclusive Study of Gender+ in External Actions. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919899345

EEAS. (2020). Human Resources Report 2019. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eeas_human_resources_report_2019.pdf

Hoijtink, M., & Muehlenhoff, H. L. (2020). The European Union as a Masculine Military Power: European Union Security and Defence Policy in ‘Times of Crisis’. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919884876

J. V. D. Vleuten (2017). The Merchant and the Message: Hard Conditions, Soft Power and Empty Vessels as Regards Gender in EU External Relations. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Merchant-and-the-Message%3A-Hard-Conditions%2C-Soft-Vleuten/a890486cd4389d89944d5eae73c5b212a0dea14a

Jacquot, S. (2015). Transformations in EU Gender Equality: From emergence to dismantling. Gender and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=4000943

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019). Handbook Sweden’s feminist foreign policy. https://www.government.se/4ae557/contentassets/fc115607a4ad4bca913cd8d11c2339dc/handbook---swedens-feminist-foreign-policy.pdf

Neumann, H. (2020). Für eine feministische Außenpolitik der EU. Internationale Politik. https://eurotradeunion.eu/documents/WGgender.pdf

Rothschild, N. (2014, December 5). Swedish Women vs. Vladimir Putin. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/12/05/can-vladimir-putin-be-intimidated-by-feminism-sweden/

Thank you for providing the cover photo Manuel Elias licensed under the terms of the cc-by-2.0.